Thai international Law Office Thailand

Specialised in Criminal Law

Listed and Trusted by Major Western Embassies

The choice of the right defence-lawyer is of paramount importance.

Our Law firm can provide you the best possible defence strategy

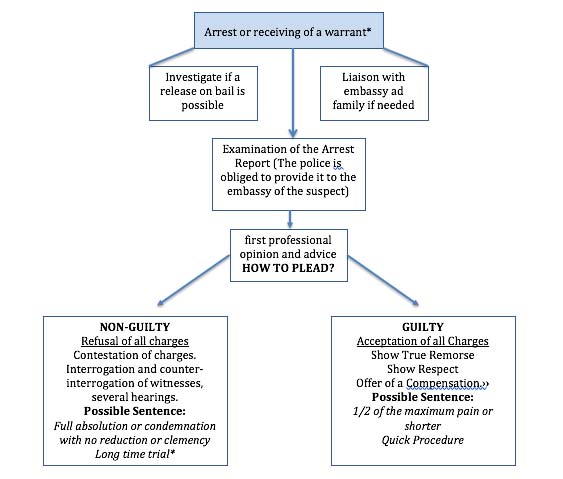

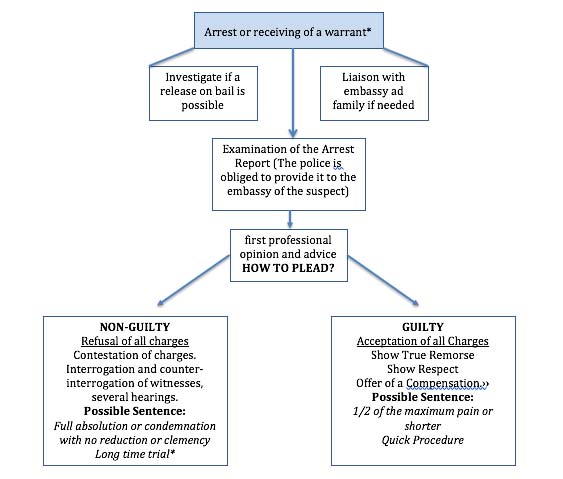

How to proceed:

Contact our expert criminal lawyer. We will assist you in your own language.

1) Arrest or receipt of an indictment

2) Investigate whether release on bail is possible

3) Liaison with the Embassy and the Family if necessary

4) Examination of the arrest report (police are required to deliver it to the suspect's embassy)

5) First opinion and professional advice

HOW TO PLEAD?

Guilty or not guilty?

A) NOT GUILTY

Denial of all charges

Contested charges. Examination and cross-examination of witnesses, several hearings.

Possible Sentence:

Complete absolution or conviction without reduction or leniency. Long procedure.

B) GUILTY (ACCEPTATION)

Recognition of all charges

Show real remorse

Show respect

Offer compensation to the victim

Possible Sentence:

Half of the maximum sentence or less.

Quick procedure.

FIRST STEPS (Defendant):

Provide us with the details of the case, together with any official documents. In case of arrest, imprisonment or detention, ask your embassy for the police-report and info. Email the Embassy giving your consent to disclose us (the social Lawyers law firm listed at the British, U.K. French, Italian and Australian embassies) any useful information the Embassy might have about the case, including the arrest report, or any other pertinent information, the place of detention, and the contact of the investigator in charge of the criminal case in Thailand

FIRST STEPS (Plaintiff/Victims):

Provide sufficient evidence. Such evidence may include proves of the wrongdoing, including documents, pictures, witnesses, videos or any other possible evidence.

We will guide you through the quickest, most effective and convenient procedure to obtain justice and compensation.

A competent member of our English speaking Pattaya lawyers' team will assist you in any binding site including police stations, immigration bureau and the court of justice in Thailand.

For Bail Bond Release and Victims Compensation

click the related links

Civil Law and Criminal Law

Differences and similarities. How to distinguish and protect ourselves according to Thai Law.

An extract from the presentation of a lesson of Dr CF Ciambrelli for the Mahidol International University, Bangkok.

In modern times, we have distinguished Civil and Criminal Law. Comforted by and bombarded with a plethora of thriller movies, crime novels and TV series, most of us give for granted to have in mind the difference between Criminal and Civil cases.

Simply put, we think: breaking the criminal law will send you to jail, while breaking the civil law will force you to pay. But, even though this very simplified distinction is not wrong, it is not quite the entire truth either, as the difference is sometimes fragile and challenging to determine, to where several prominent jurists and philosophers of law deny the existence of a clear distinction between Civil and Criminal law at all, especially when it comes to economic damages.

What is sure is that the two branches of the law often intersect and intertwine as two railways going in the same direction but ending in different stations or, right the opposite, running on different rails and ending at the same post! In Thailand, because of the peculiarity of the judicial system, I would venture to say that the “cut-off”, this dividing line, is even thinner than in the West.

Leaving alone (for now) the most blatant and striking situations where the distinction between criminal actions and civil defaults appears evident, as in the cases of murder, robbery, and violence, to give some examples, let’s see what happens when the offence or the default causes economic damage to another person. It will surprise you how thin the distinction is most times and how most of people have got it wrong.

The Thai Civil and Criminal Codes.

Civil law in Thailand is regulated by the Civil and Commercial Code, while the Criminal Code disciplines criminal law. The distinction though appears to be clear and definite, not just apparent or theoretical. More precisely, in Book one, Title One, Section 5 of the Civil and Commercial Code, we read: in exercising the rights or performing the obligations, every person shall act in good faith, bona fide.

On the other hand, in Book one, Title One, Chapter One, Section One of the Criminal Code, we read, “According to this Code Dishonesty means to acquire any advantages, for himself or herself or for other persons to which he or she is not entitled to by law.”

By the letter of the law, it appears that the distinction between civil default and a criminal action lies in the concepts of “bona and mala fide” and in the one of “honesty”.

So, if somebody asks you for a loan promising to give it back to you, but he doesn’t, is it criminal or civil? Or if you sell goods to somebody who promises to pay you in several instalments, then he damages the products and doesn’t pay you, is it civil or criminal?

And in these cases, should you seek the assistance of a civil or criminal lawyer?

Shall you report the facts to the police or directly to the court?

You might say: it depends if he was in good faith or in mala fide if he was honest or dishonest. But how can we prove it?

How can we prove for example, that the person to whom you generously conceded a loan had never had the slightest intention to give it back, in which case, it would be mala fide, and he should be sentenced to jail?

Compoundable and non-compoundable offences.

The first watershed, the distinction between compoundable and non-compoundable offences, will certainly help us to start dispelling some doubts. While a civil action or infraction is always compoundable and can be punished only upon an action of the damaged part, called plaintiff (jot in Thai), a criminal offence can be compoundable or not compoundable. By the letter of the law and by definition, a compoundable criminal offence is an offence that we can “forgive”, renouncing demanding any punishments of the perpetrator and giving up any compensation. If, for instance, somebody deceives you and misappropriates your assets, you can decide whether to prosecute him/her or not, or you can renounce the action even after a trial has started.

To make a more blatant example, according to the Thai Criminal Code, the crime of “rape” which can be punished with 4 to 20 years of imprisonment if it is not committed in public or causing grievous body harm or death, “it shall be a compoundable offence” (section 281 of the Thai Criminal Code).

Let’s see then what happens in real life. What are the effects and the consequences of our actions, how to protect ourselves, and where should we seek help?

Second part.

While in the first part of this article, we have tried to clarify the differences between Civil and Criminal Law and between a criminal and a civil offence or a default, today - as promised - we will try to understand what are "the effects and the consequences of our actions and how to protect ourselves best.

"The choice of the proceedings: criminal or civil?

Whether we might be the "victims" of the most obnoxious crime or merely the “victim” of the breach of a contract, to obtain a just compensation, we shall, in any case, recur to a Court of Law. In fact, nobody can take the law into his own hands. But, even though I believe that most of us, in theory, totally agree with this fundamental principle, you would be surprised to see how the majority of people do not have this concept clearly in mind when it directly affects them. We feel like victims, and we believe that we have the right to justice, but only a court of Law (very rarely the police and only in case of severe and evident crimes), can oblige the offender to respect the Law, never the "presumed" victim. All this implies that the first choice we are called upon to make is about the right course of proceeding: shall we recur to a civil or a criminal court? It might seem a rhetorical question, but in many circumstances and everyday life, it maybe not be so easy to answer; nevertheless, our choice will indeed be of paramount importance (especially in Thailand) due to the legal and practical consequences of the proposed action.

If it is true, as we have emphasised in the first part of this article, that sometimes the dividing line between Civil and Criminal Law is very thin and difficult to determine, in practice, it can make an enormous difference, especially for the following principal reasons:

- A criminal proceeding (trial) is usually faster than a civil one

- The fear of being sentenced to prison can be huge leverage to oblige the defendant to compensate for the damage caused to the victim.

- The Thai legal system contemplates constant research of mediation between the parties, the defendant (supposed offender) and the plaintiff (supposed victim). The defendant's acceptance of guilt and the compensation of the caused damage can drastically reduce the penalty, even in the most severe, non-compoundable charges.*

At the other end:

- A Civil lawsuit can last years (even though nowadays the works of the court is indeed much faster than in the past)

- A Civil sentence doesn't automatically guarantee that the plaintiff will get compensation without a separate (often difficult and costly) action to reinforce it. Most importantly, he/she won't get anything if the defendant has no assets to be seized! In other words, apart from our moral scruples, it might often be preferable to seek criminal charges against the perpetrator anytime he/she has committed a crime causing the other part economic damage, provided we can show a stable balance of evidence.

What we should imperatively keep in mind before deciding what might be the most effective and appropriate action.

Criminal Charges:

-A sentence of guilt against the perpetrator of a crime that has caused damage to his victim doesn't-necessarily imply an economic compensation for the victim.

From a civil point of view, the two matters are entirely and profoundly distinguishably: a verdict of guilt in a criminal trial will ethically punish the perpetrator for his misdoing but not necessarily assure any compensation for the victim, which shall be established separately by a civil court unless a civil lawsuit has been contemporarily "brought into the criminal proceeding".

- A criminal proceeding will, by law, suspend and interrupt any proposed civil lawsuit.- A criminal complaint can be submitted directly to the court or at a police station. The proceeding would be much quicker in the first case, and the plaintiff must present evidence against the defendant. In the case of acquaintance, the defendant could legitimately counter-propose a complaint for defamation, demanding, in turn, criminal punishment and compensation.

- A criminal charge can be proposed to the police station as well. Reporting a crime at the police authorities would, in the majority of the cases, eliminate the risk of a counter-suit for slandering unless the "presumed" victims would have counterfeit or forged evidence or lie to the police officers. However, reporting a crime at the police station won't always guarantee a speedy court trial against the offender.

- A criminal complaint will not exclude the possibility of a civil action even in case of acquittal of the defendant, but it will slow down the process. On the other hand:

- A civil lawsuit can only be filed directly to the court, not at the police station.

- A civil lawsuit will not entail the possibility of a criminal counter-suit for defamation.

- A verdict of guilt will not restrict the defendant's freedom; he/she will respond only with his/her assets. The choice of the right lawyer. In conclusion, we might say that, in most cases, only a competent lawyer can guide you through the options for the appropriate proceedings. In fact, if it is true that pressing criminal charges - when and where possible - can speed up the procedures and compel the perpetrator to compensate for damages quickly, it is also true that it will not necessarily entail the obligation to pay the victim and, as we wish to underline again, in case of lack of or insufficient evidence, it can involve the risk of a counteraction by the defendant for defamation.

Link to Criminal cases

Everybody is equal before the law, but...

Committing a crime in Thailand, a passage to hell.

Extract from an article of Dr Carlo Filippo Ciambrelli

Let me start by the end or, as we may say, let's grasp the bull by the horns. Thailand, the so-called "Land of Smiles", it's definitely one of the worst places in the world to commit a crime.

The laws governing a country are divided into two major legal systems: Common Law and Statutory Law.

In countries like Thailand, governed by the "statutory law system" the laws are clearly "codified" or "listed" in a sort of legal-Bibles: the penal (criminal) Code and the Civil Code.

In the Penal Code (link to Thai Penal Code), practically every possible crime is well described and "equipped" with the indication of the relative minimum and maximum applicable penalty. The difference between the minimum and the maximum penalty is the only feasible discretion conceded to judges and juries.

Consequently, in the majority of the countries adopting the "rigid-although-clear" statutory law system (S.L.S.) the judge will apply the law and impose the penalty in relation to the circumstances, including a possible admission of guilt given to the court by the defendant, within limits clearly written in the Code. And here, we find the first huge difference between the Thai and the European S.L.S.: In Thailand, a confession will practically, even though not automatically, in most of cases, cut the penalty by half. Including the "minimum applicable penalty". Furthermore, in Thailand, as in Common Law countries, it is possible to ask (apply) for a bail bond and remain free at least until the first-degree sentence. At this point you might think "the title of this article must be a mistake", but ...I'm afraid that it is not so, not at all!

To make things a bit brighter, let's "go back" to the beginning and see what happens in real life if you are accused of a crime. Let's see how things can be drastically different in the Western world.

The first authority called to “judge” upon the receiving of a crime report is the police. No coroner, no investigating judge. The police will decide, for instance, if an autopsy is necessary and, more importantly, if the proof or the clues against the suspect of a crime are enough to arrest him, to transmit the case to the court and if it is possible to release him or her upon the payment of bail.

Should the police deny the bail, the “defendant” will be transferred to a remand awaiting the judgement. He/she can, therefore, apply for a new release on bail directly to the court with uncertain results.

I don't know if you have ever had the chance to visit a remand. In my experience as a court interpreter and "volunteer upon request of the embassies", I often had such a privilege. I can tell you that they are not precisely holidays-resorts! To say the least, you would not enjoy being there.

Furthermore, not to scare you, but instead, to warn you (a man forewarned is a man forearmed), you would better consider that there are a considerable number of crimes that do not foresee the possibility of being released on bail at all, regardless of the "solidity" of the accusations.

The main criteria adopted to deem if a suspected culprit can benefit from a release on bail are the possibilities of his/her escape (obviously much higher if the accused is a foreign national), the chance of evidence-tampering and the alleged social dangerousness of the suspect. All crimes against society, the governments (not only the Thai government), the state institutions etc., for instance, currency counterfeiting, credit card forgery, to not mention lease-majesty, leave very little space to achieve a temporary release on bail. Furthermore, such kind of crimes is very severely punished in Thailand.

Out of metaphor and to clarify the concept, we can say that it would be easier to release on bail somebody accused of "attempted murder" rather than of one of the crimes mentioned above.

I suppose (and hope) that whatever we have written today will never regard our readers, but what happens if someone falsely or wrongly accuses you? What about if you are the victim of fraud or an error? How long will a trial last?

Answers are coming soon...

THE IMPORTANCE OF CHOOSING A LAWYER PROFICIENT IN YOUR LANGUAGE

When facing criminal charges in Thailand, choosing the right criminal lawyer who can effectively represent your interests and provide you with the best possible outcome is essential. However, finding a competent and reliable attorney can be daunting, especially for foreigners unfamiliar with the local legal system and language barriers. Therefore, selecting a lawyer who speaks your language, understands the unique challenges that foreigners face, and comes highly recommended by your embassy is crucial.

Thailand attracts millions of visitors each year and a notable number of expats. Unfortunately, some visitors may find themselves on the wrong side of the law, facing criminal charges ranging from minor offences to serious crimes. Regardless of the nature of the charges, it is crucial to have a competent criminal lawyer who can represent your interests and protect your rights.

When selecting a criminal lawyer in Thailand, it is paramount to have a full, deep and complete understanding of the client-lawyer; therefore, unless you are very fluent and have a deep, accurate knowledge of the Thai language. Language barriers can significantly hinder communication between the lawyer and the client, resulting in misunderstandings that can adversely affect the case outcome. Therefore, choosing an attorney who can speak your language fluently and explain complex legal concepts and procedures clearly and concisely is vital.

Another essential consideration when choosing a criminal lawyer in Thailand is their familiarity with the local legal system. The Thai legal system can be complex and confusing, particularly for foreigners unfamiliar with the country's laws and regulations. Therefore, selecting a lawyer with extensive experience in handling criminal cases in Thailand who is familiar with the local legal system and practices is vital.

In addition to language proficiency and knowledge of the local legal system, choosing a criminal lawyer who understands foreigners' unique challenges when dealing with the Thai legal system is crucial. Foreigners may face additional hurdles, such as cultural differences, language barriers, and a need to understand the local legal system. A competent criminal lawyer familiar with these challenges can provide invaluable assistance in navigating the system and ensuring that your rights are protected.

One way to find a competent criminal lawyer in Thailand who meets these criteria is to seek recommendations from your embassy. Embassies often maintain lists of recommended lawyers proficient in the client's language and have experience handling criminal cases. These lawyers are typically vetted and recommended based on their track record of success in representing foreign clients and their understanding of the unique challenges that foreigners face.

Working with a criminal lawyer recommended by your embassy can provide additional benefits, such as access to legal resources and support during the legal process. Embassies can provide guidance and assistance in dealing with local authorities and can help ensure that your rights are protected throughout the legal proceedings.

Choosing the right criminal lawyer is essential when facing criminal charges in Thailand. A competent and reliable attorney who speaks, your language understands the local legal system and is recommended by your embassy can provide invaluable assistance in navigating the legal system and ensuring your rights are protected. Therefore, conducting thorough research and choosing a criminal lawyer who meets these criteria is crucial to achieving the best possible outcome for the case.